overview

In his novel Discourse on Method, French philosopher and mathematician Rene Descartes said, "But what is a thinking thing?" This paradoxically complex yet straightforward query echoed the voice of fellow philosopher Plato, who, centuries before, insisted we must turn our attention inward to "find someone who will in some way make us better" (Scott, 2006). This notion of a self-reflective consciousness has been the focus of philosophers' eyes for centuries. However, it was not until the 1970s that J.H. Flavell first gave this cognitive phenomenon its name; metacognition. In metacognition, conflicting theories and research abound, including in its evolutionary origins—some say it allowed early hominids to imagine new and different worlds, or perhaps it was to predict the behavior of others (theory of mind) (Frith, 2012; Metcalfe, 2008). Evolutionary suppositions aside, those with higher developed metacognition have a greater level of intelligence (Sternberg, 1984). As this paper will show, understanding metacognition and the nuances of learning styles provides valuable guidance for designers, as well. The virtual reality game Saints and Sinners® will then be analyzed to demonstrate the importance of understanding these design heuristics within a pseudo-life-critical environment.

metacognition

Though J.H. Flavell first coined the term metacognition, it was based on the stage-setting foundational work of earlier psychologists like Inhelder and Piaget (1958). Metacognition is the parallel, executive process that forms the cyclical framework that drives the assessing, planning, monitoring, and evaluation of one's learning. This introspective, “thinking about thinking” makes us adaptable, thinking human beings (Sternberg 1984; Jansiewicz, 2008; Ambrose et al., 2010).

Taxonomy

Metacognition concatenates three distinct categories; metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive regulation, and metacognitive experiences (Flavell, 1979; Papaleontiou-Louca, 2019). Metacognitive knowledge is the awareness of and about an individual's prior knowledge (Pintrich, 2002; Tarricone, 2011) and is determined by declarative knowledge (knowledge of self), procedural knowledge (knowledge of strategies), and conditional knowledge (knowledge of tasks) (Pintrich, 2002; Tarricone, 2011). Metacognitive experiences are the implicit or explicit thoughts, intuitions, perceptions, feelings, and judgments an individual becomes aware of during problem-solving and task completion (Efklides, 2006; Tarricone, 2011). Finally, metacognitive regulation describes how learners monitor and control their cognitive processes through planning tasks and resources, monitoring task performance, and evaluating task outcomes (Brown, 1987; Azevedo & Aleven, 2013). The working memory behind regulation also helps eliminate task-irrelevant noise (Komori, 2016). Nelson (1990) explained that regulation relied upon bottom-up processing (error detection monitoring) and top-down processing (planning and evaluating error corrections and resolutions). This interplay of processing, working memory, and prior knowledge underscores metacognition as a complex yet advantageous phenomenon leveraging the harmonious interconnection of our perceptual and cognitive systems.

individual learning preferences

Learning is a complex process impacted by the learner's willingness and ability to learn, the environment, instruction quality, and learning style (Lo et al., 2012; Jonassen & Grabowski, 2012). One obstacle in expounding learning into any didactic form is the proliferation of seemingly disparate constructs, inconsistent nomenclature, and ever-increasing systems of measure. Moreover, some terms, such as learning styles, have been described as being both structured (unchangeable) and dynamic (adaptable) (Riding & Cheema, 1991). Cognitive ability, cognitive control, cognitive style, learning style, experience, and environment are just a few of the terms seen within these models. This paper will focus on cognitive style and learning style, though cognitive ability and control will be touched upon briefly and only to set their foundation. Cognitive ability sometimes referred to as intelligence, refers to the degree to which individuals can interpret and learn from the information around them. (Jonassen & Grabowski, 2012). Cognitive control is a critical factor in scholastic success. It represents the flexible give-and-take between emotion, attention, thoughts, and behaviors that form a decision (Hsu & Jaeggi, 2014; Koff, 1967; Miller & Cohen, 2001).

expert versus novice

Approaches to problem solving and learning are also experience-dependent. Experts have access to well-developed declarative and procedurally based knowledge maps and schemas that guide learning and problem-solving (Chi et al., 1981). Metacognition is integral in selecting, monitoring, and evaluating these strategies (Moortgat, 2002). Though they may have topic-specific declarative knowledge, Novices lack procedural knowledge preventing them from making the necessary connections and leading to a trial and error approach and increased cognitive load—or their limit to process new information. ("Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation," 2017; Chi et al., 1981).

Cognitive styles and learning styles

Nowhere is the aforementioned convolution more evident than the veritable cornucopia of concepts and contradictions between cognitive style and learning style. Depending on your lean, they are either separate or the same, apropos or irrelevant. Cognitive styles and learning styles represent an individual's preferred way of learning; it is how rather than what a learner thinks (Jonassen & Grabowski, 2012). Cognitive styles are typically bi-polar "either-or" dimensions. For example, the cognitive style, "visualizer/verbalizer," describes individual preferences to learn via pictures or words. Likewise, the "active/reflector" model explains that some individuals prefer to learn by actively engaging while others prefer to engage only after collecting all requisite information (Jonassen & Grabowski, 2012; Riding & Cheema, 1991; Stash, 2007). Unlike cognitive styles, learning styles typically are not "either-or" dimensions but rather measured across multiple characteristics. For instance, Kolb's quadrant-based Learning Style Inventory assigns learners along a spectrum based on their tendencies to be divergent, assimilators, convergers, or accommodators (Kolb, 2014). Kolb posited that learners grasped and transformed information into knowledge through varying degrees of conceptualization, reflection, and experimentation. (Jonassen & Grabowski, 2012; Kolb, 2014). There are other models, such as Dunn & Dunn and Gregorc, but Kolb's model of "conceptualization, reflection, and experimentation" brings to mind the reflective nature of metacognition and offers a timely bridge between it and learning styles.

Learning and metacognition

In a study with learners in virtual environments (VR) showed knowledge acquisition was directly influenced by student learning styles (Yildirm & Zengel, 2014). Although Felder (2010) stresses the importance of knowing your learner’s learning style, Zhou (2011) cautions that serving information precisely as the learner prefers creates an obstacle-free landscape preventing metacognitive interventions. Though, style awareness could engender metacognitive activities by allowing learners to reflect and strategize on known weaknesses (Rahman et al., 2011; Robinson et al., 2022). Metacognition is important for students to become self-regulated learners; though students have a general concept of metacognition, they might struggle to develop strategies that positively impact their overall learning process (Shannon, 2008; Winne, 2010). A study with 104 chemistry students of varying grade levels showed that implementing metacognitive strategies, particularly regulation, e.g., managing time, goals, and strategies, improved their comprehension of concepts that were typically difficult to understand (Ramadhan & Pratana, 2020). By incorporating metacognition activities such as asking questions, "What do I know?", "What don't I know?", "What do I need to know?" or "Is this important for my goal?" learners become more self-aware and start making connections to prior knowledge (O'Neil, 2016; Shannon, 2008). Other methods, like scaffolding, provide students with cognitive supports that decrease cognitive load and increase metacognitive skills making them more self-sufficient and less reliant on future guidance (Ambrose et al., 2010; López-Vargas et al., 2017). However, metacognition is not a one-size-fits-all application nor is the development between abilities balanced. Shannon (2008) showed that although teaching students metacognitive strategies helped them be more curious and self-directed learners, it also showed its demonstration needed to match their learning style. Additionally, metacognitive awareness typically develops around age five, while some abilities, like monitoring, begin around age nine (Kleitman & Gibson, 2011; Veenman & Spaans, 2005).

Designing for learning and metacognition

Creating one experience that matches all learning styles would be a massive undertaking, if not wholly impossible. Solutions that alter information based on known learning style traits have been proposed. Lo et al. (2012) used auto-generated learning styles to alter information display. These learning styles were created based on the learner's internet browsing history. Due to the exhaustive set of configurable possibilities, this test limited itself to style subsets within the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Ausburn & Ausburn (1978) presented a less-automated but possibly more plausible adaptive model that utilized conciliatory supplantation to alter information display. For example, a learner with the "field-dependent" learning style might have difficulty discerning detail in a highly complex and dense display, but a designer could afford, through filtering, the ability to hide task-irrelevant detail.

Adaptive systems are promising but unplausible until they accommodate a more significant subset of learning styles. This means the act of "understanding" is the designer's responsibility, not the learner's burden. Expecting a learner to engage in a cycle of metacognitive self-reflection and goal setting while fussing with a life-critical application is both shortsighted and irresponsible. When learning styles are known they should be utilized to drive design decisions, particularly with life-critical applications.

One way to do this is to turn user data into qualitative representations—e.g., personas. Unfortunately, designers have a proclivity towards ego-centric problem-solving. However, a study measuring designer traits between empathizing (EQ) versus systemizing (SQ) showed that those with higher levels of the EQ style were more likely to rely on personas when faced with design challenges (Marsden et al., 2017). Additionally, López-Mesa & Thompson (2006) demonstrated that measuring colleague learning styles allowed companies to leverage style strengths and create specialized teams that better meet project needs. This research provides insight into the power of understanding designer and team dynamics and how they can be leveraged to drive better design outcomes.

However, better design should not be predicated upon having access to learning styles. Thankfully, the underlying mechanisms of metacognition offer guidance. When visitors enter a site, they do so with a series of questions, such as, "What goals do I have?" How do I achieve them?" "How do I use this system?" "What do I know about this interface?" (O’Neil et al., 2016). These questions drive their metacognition to create connections between prior knowledge and the new information in front of them (Chiquito, 1994). Metacognition maturity and strength vary and those with lower levels typically have trouble regulating their metacognitive functions in online learning environments, causing more significant confusion and time to complete goals (Lee & Baylor, 2006). So creating environments that offer cognitive support, e.g., helpful affordances, familiar metaphors and visual cues, proper hierarchy, intuitive architecture and navigation, feedback and wayfinding, etc., will help visitors with attention regulation, strategy selection, task completion, and goal monitoring (Jones et al., 1995; Kirsh, 2005, Lee & Baylor, 2006). These methods support assimilating new information with prior knowledge and increase speed and accuracy while decreasing cognitive load (Chiquito, 1994; Kirsh, 2005). Metacognition also represents a process for the designer. Kavousi et al. (2020) showed that designers engaging in introspective metacognitive activities like strategizing solutions, analyzing tasks, and goal setting and novel idea generation, creating a framework for early design phases (Kavousi et al., 2020).

Design review

Saints and Sinners® is a virtual reality game modeled after the television series, The Walking Dead®. The premise is simple; survive by any means necessary—avoid zombies, dodge marauding gangs of survivors, find food, and collect weapons. This paper will explore the designers' explicit and implicit learning techniques implemented to help players learn, reduce cognitive load and be more efficient players.

instruction and environment

The game starts by taking the learner through a training course where he learns to interact with the world around him. In figure 1, he "speaks" with survivors

(experts), who guide him through various lessons against zombies that have been restrained and rendered harmless. Experimenting and exploring varying tactics in a safe, risk-free environment is a foundational element of metacognitive growth.

Additionally, O'Neil et al. (2016) showed that scenario-specific guidance engenders better performances and makes knowledge more easily transferable to other tasks.

figure 1: Your expert guide (Tutorial Man) steps you through each exercise to assure your character can survive in the apocalypse. Image still by author.

limiting cognitive load

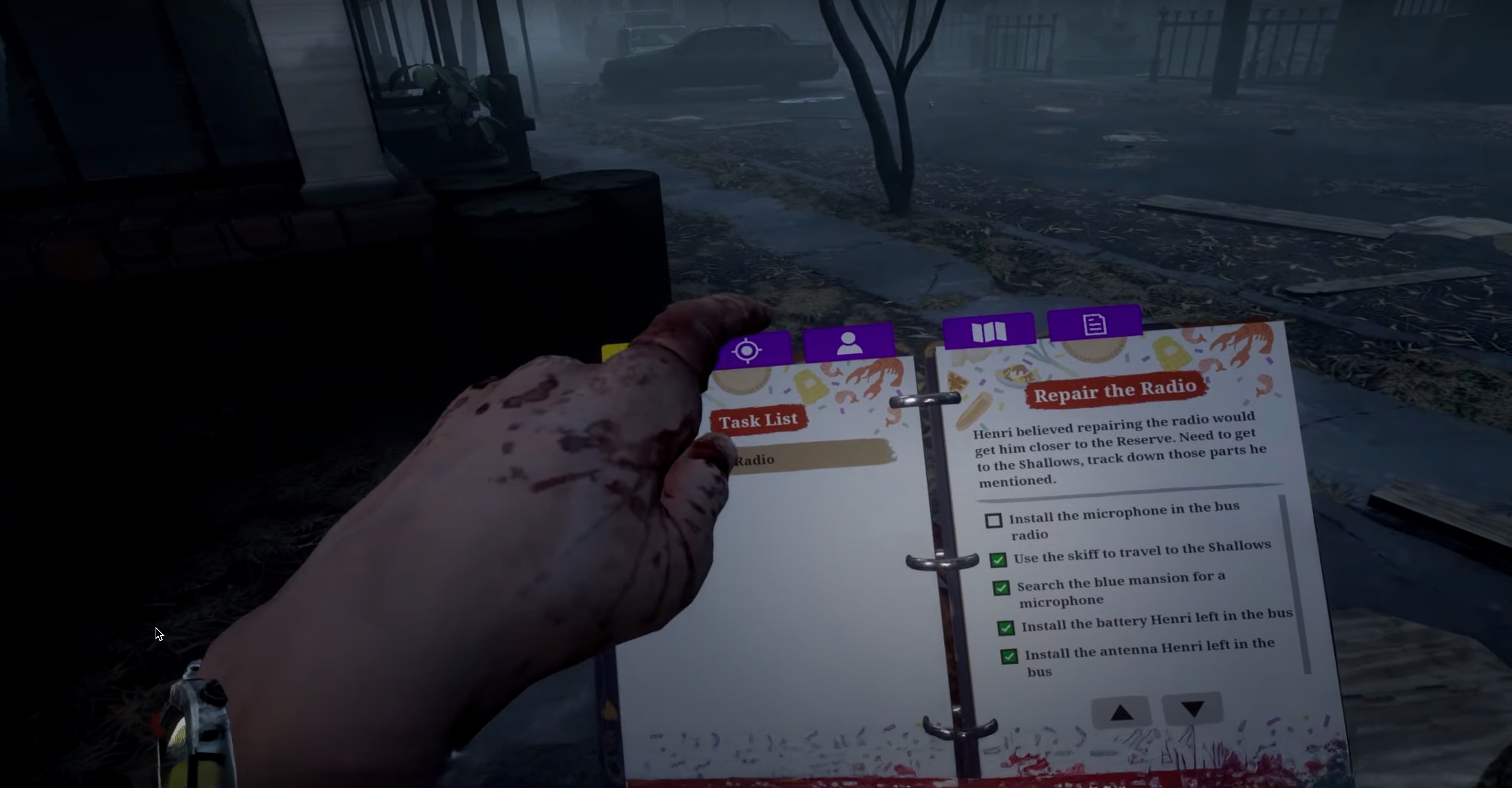

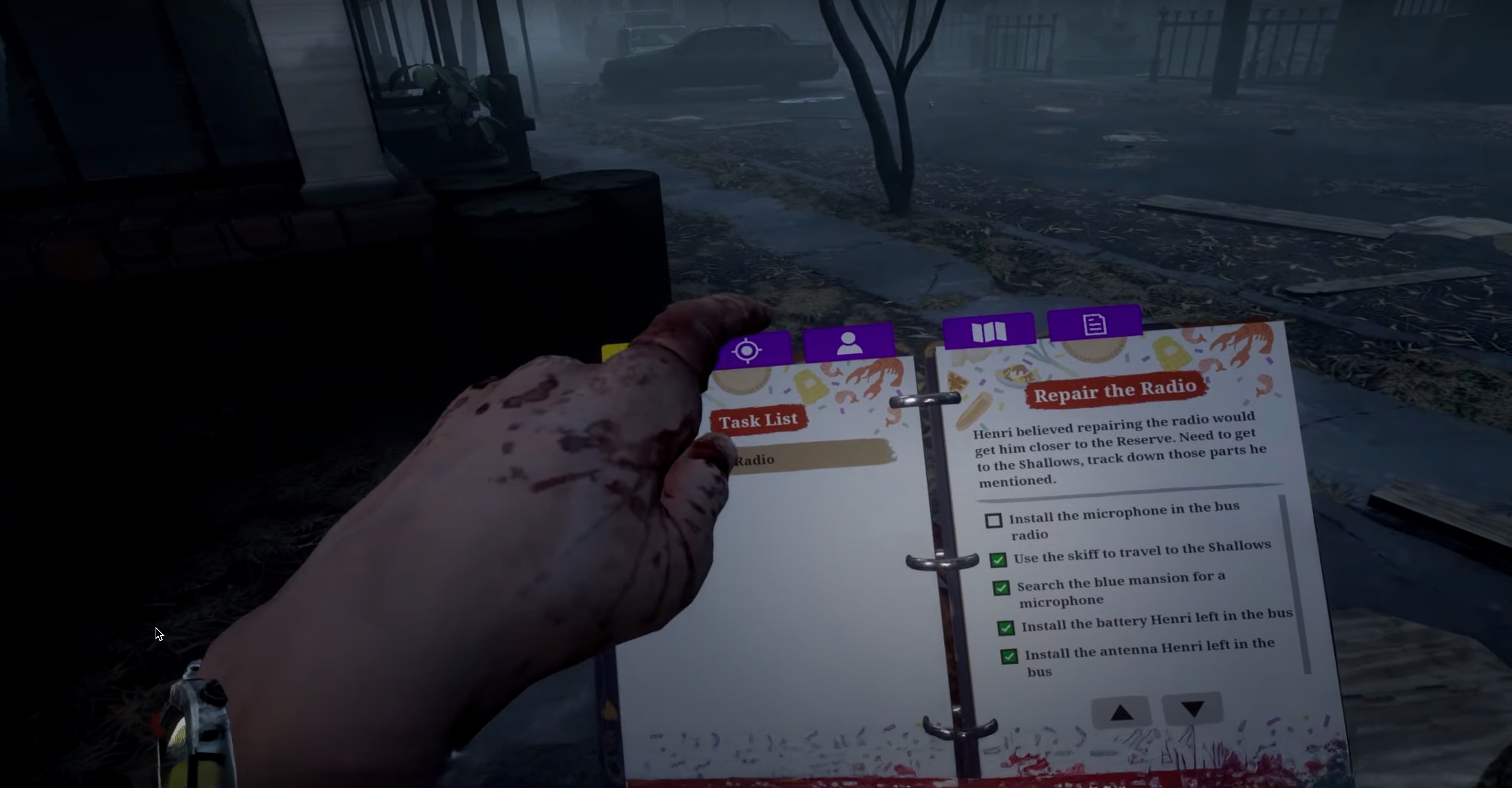

At the beginning of each "round", the game character receives assignments from collaborators via short-wave radio transmissions or through randomly dropped letters.

As depicted in Figure 2, these assignments are automatically cataloged, tracked, and

updated in the character's notebook. This feature allows the learner to save valuable cognitive load for more pressing tasks, like navigating through the streets and

buildings of each level.

figure 2: Task lists start small but as the level progresses, right, items are added and checked off. Not having to remember each task reduces cognitive load for the gamer and allows him to focus on surviving. Video still by Vizm.

increasing cognitive load

Believing the mission is complete, the learner steps out only to face an ambush by a militia squad. As figure 3 shows, a chaotic gunfight ensues, causing the learner’s anxiety—and cognitive load—to spike. Even after seemingly dispatching the militia, the tension doesn’t ease. Ominous background music warns that the threat isn’t over. The learner scans their surroundings, bracing for the unexpected. When he can hear a zombie closing in from behind, the situation becomes even more chaotic. Struggling with weapon management, the learner misses shots they would normally hit and becomes

disoriented, even ejecting a magazine by mistake instead of firing. The steadily increasing cognitive load amplifies the sense of stress and urgency, creating a deeply immersive and realistic experience.

figure 3: The effects of increased cognitive load can be leveraged to create more immersive experiences. Video by author.

task completion

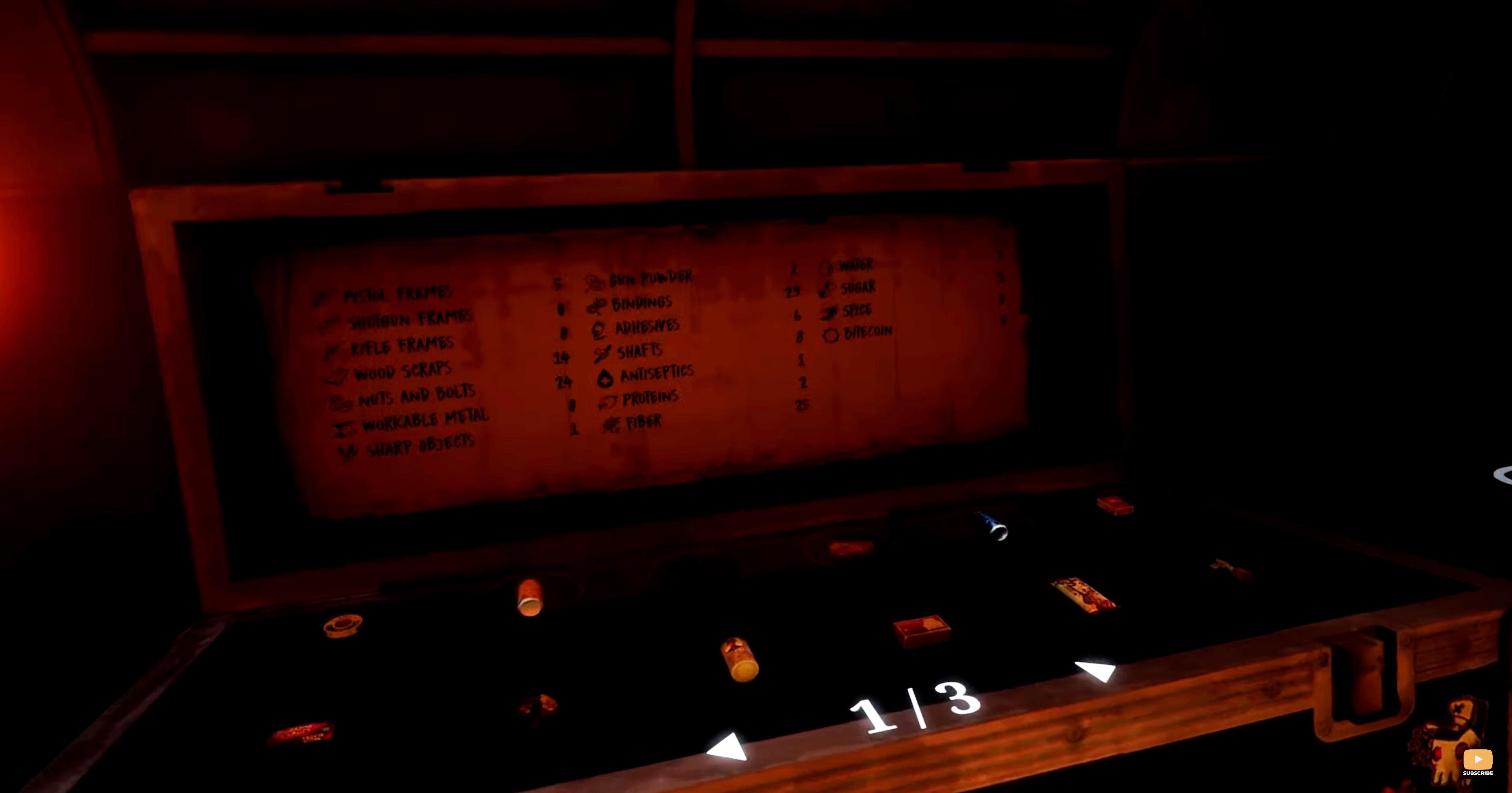

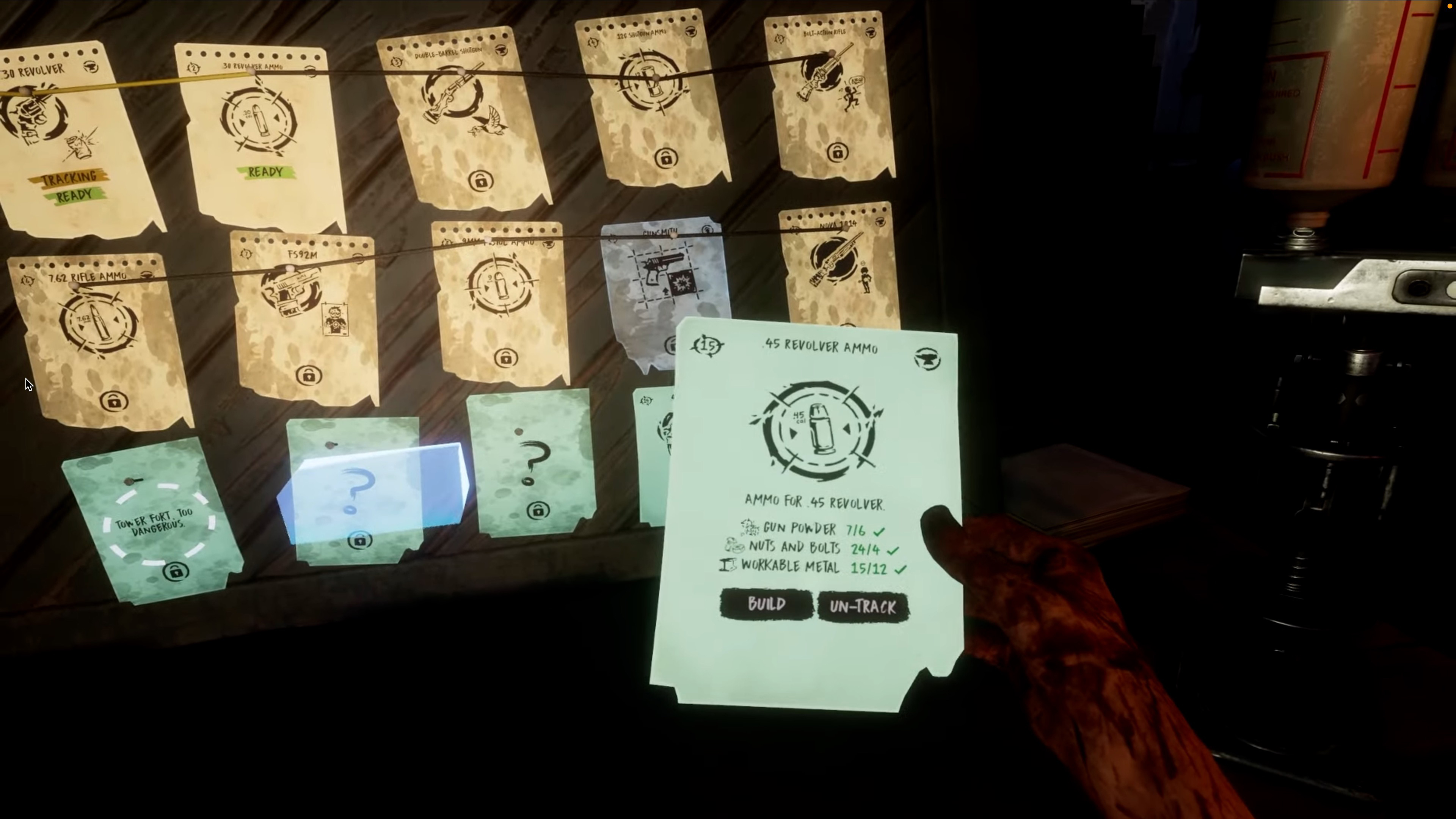

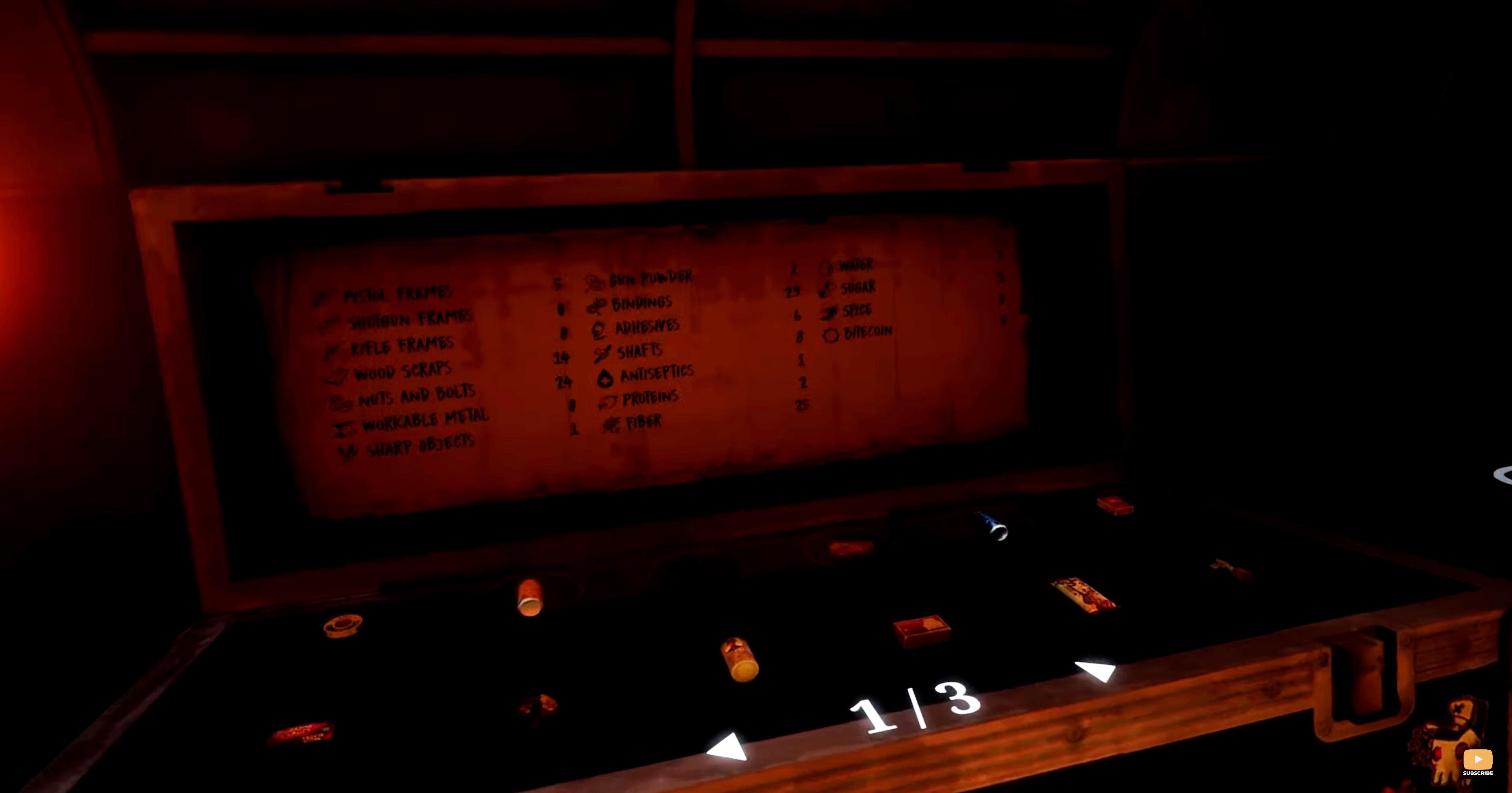

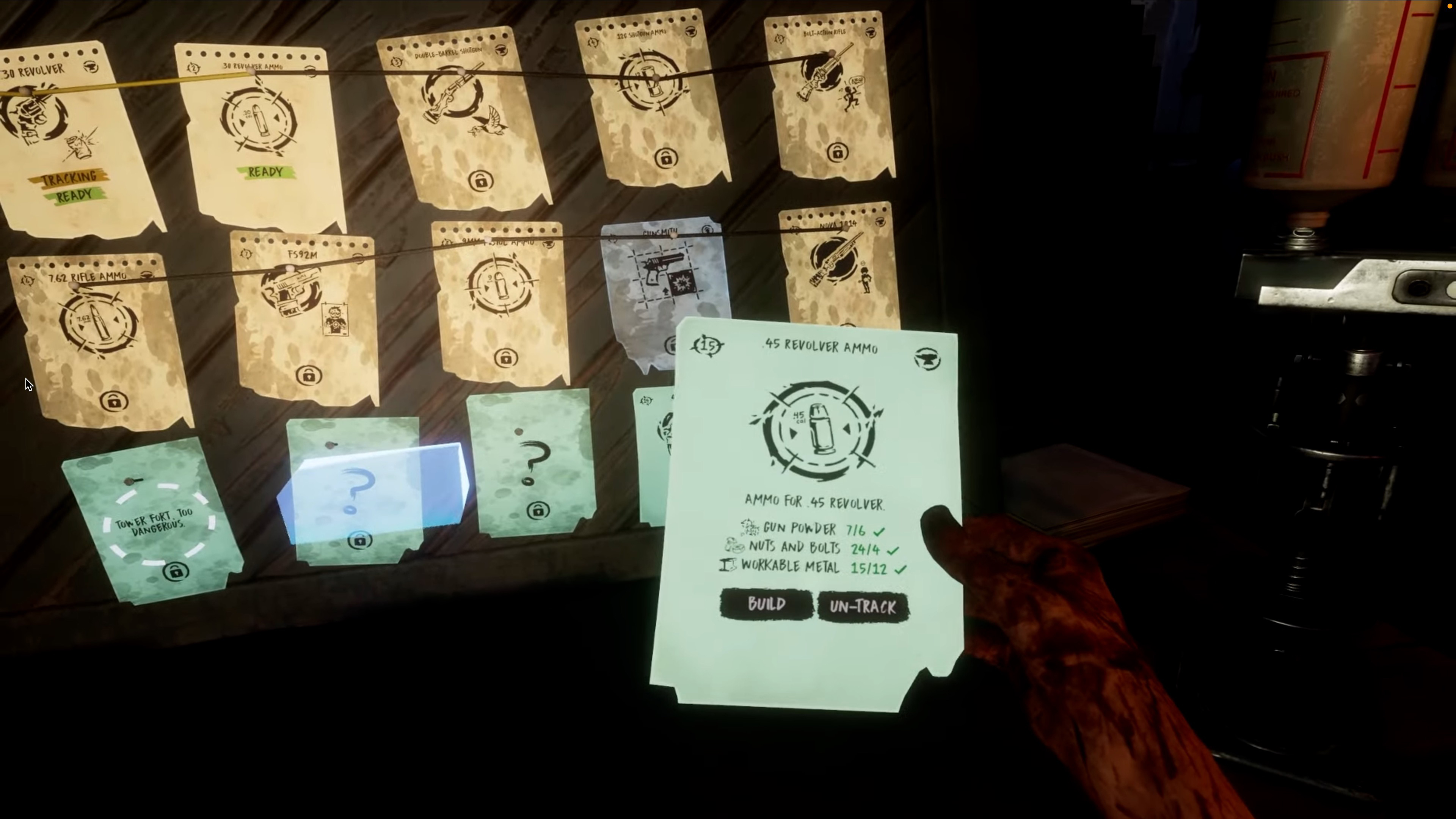

Progress is also measured in less overt ways. After each level or mission is

completed, the character returns to the safety of his base where items can be tallied, stored, and/or recycled into gear for future missions.

Seeing what has been collected, what is available, and what remains to be collected as shown in figures 4.1-4.3, allows the gamer to assess his progress and create strategies and goals moving forward.

figure 4.1: The recycled value of scavenged or worn-out gear is displayed in terms of “ingredients” which are used to build other items, like, food, first aid, and weapons. Video still by Vizm.

figure 4.2: A running tally of all collected ingredients. Video still by Vizm

figure 4.3: Each card displays how many ingredients are collected vs required. Onceenough are collected, the item is buildable. Video still by Vizm.

scaffolding

Scaffolding is pivotal in fostering self-sufficiency among learners. To help guide learners towards their goals, designers will integrate “supports” into an experience. Task completion in Saints and Sinners often requires the learner to seek alternate entry into buildings through less than obvious affordances — especially for novices.

To scaffold the experience, designers deliberately marked these inconspicuous affordances with white paint so the implied interaction becomes more obvious. As figures 5.1-5.4 demonstrate, even without being specifically instructed, the learner knows these elements are meant to be interacted with. Having learned these markings signaled an interaction, the learner is now self-sufficient.

figure 5.1: The white markings running up the red building forms a ladder like

pattern. For the leaner, this pattern and its diversity against surrounding objects signaled a climbable object. Video still by RabidRetrospectGames.

figure 5.2: Most bookcases in the game can not be interacted with, so designers applied white markings along each shelf of this bookcase to tell the learner it can be grasped and climbed like a ladder through the hole in the porch ceiling. Video stills by RabidRetrospectGames.

figure 5.3: the markings on the drain pipe on the blue house are less obvious but having seen the earlier example, the learner needs less direction to know that this drain pipe is climbable. Video still by RabidRetrospectGames.

figure 5.4: here, the learner has reached one of the final levels of the game. after failing to find a way into a key building, the learner knew the actual way in must be accessible only through a “scaffold” entrance. Here, it’s found by scaling and traversing multiple surfaces. Video captured from RabidRetrospectGames.

Conclusion

In our increasingly complex and information-rich world, where experiences span a

multitude of modalities, the necessity of understanding and catering to the user's cognitive and learning styles becomes paramount. This paper has demonstrated that by embracing a deeper awareness of these styles and the practices that encourage metacognitive activities, designers can create more engaging, effective, and

intuitive user experiences.

Through the analysis of Saints and Sinners, we've seen how metacognitive principles can be skillfully integrated into design to enhance learning and user engagement. The game's approach to instruction, environment, goal setting, task completion, and time management not only serves the purpose of gameplay but also aligns with the cognitive processes of the players. It showcases the practical application of metacognitive strategies, such as scenario-specific guidance, pattern recognition, and strategy formulation, in enhancing the learning curve and overall experience for users.